If not for a tragic twist of fate, baseball fans today might be recalling Charlie Peete much like they do Lou Brock or Curt Flood as being an integral part of Cardinals championship clubs.

An outfielder and minor league batting champion in the Cardinals system, Peete was on the cusp of becoming a prominent player in the majors.

An outfielder and minor league batting champion in the Cardinals system, Peete was on the cusp of becoming a prominent player in the majors.

On Nov. 27, 1956, four months after he made his major-league debut with the Cardinals, Peete, 27, was killed in an airplane crash in Venezuela. His wife and three children died with him.

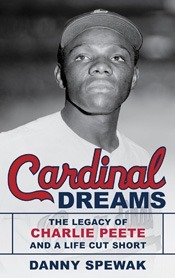

Author Danny Spewak has written a biography of Peete. It’s a compelling page turner. If you appreciate good writing, original research and a gripping yarn, this book is for you. It’s “Cardinal Dreams: The Legacy of Charlie Peete and a Life Cut Short.” Order a copy on Amazon by clicking on this link.

Here is an email interview I did with Danny Spewak in February 2024:

Q: Congratulations on the book, Danny. As Jack Buck used to say, it’s a winner. What prompted you to choose Charlie Peete as the subject?

A: “Thank you so much, Mark. I’m a St. Louis native, lifelong Cardinals fan and avid reader of your site. Charlie Peete’s name first came on my radar after the tragic death of Oscar Taveras in 2014. The circumstances surrounding the loss of Taveras, a promising young Cardinals outfielder, shared many similarities with Peete’s passing in a 1956 commercial plane crash. More recently, when I began researching topics for my second nonfiction book, I revisited Peete’s story and discovered an incredible legacy worth sharing. Peete is not widely known to Cardinals fans, but he’s one of the franchise’s greatest ‘what-if?’ stories, the kind of player who could have developed into a real star if not for his premature death. More importantly, Peete played a key role in the integration of the Cardinals in the 1950s and, as the book argues, laid the foundation for the groundbreaking World Series teams of the next decade.”

Q: What qualities made Charlie Peete a top prospect?

A: “The Cardinals viewed Peete as a classic five-tool prospect and were thrilled by his performance in the minor leagues after drafting him in late 1954. Bing Devine, who eventually became the Cardinals general manager, singled out Peete as an example of how an organization could build a winning franchise through the draft process. At Class AAA stops in Rochester and Omaha, Peete displayed an impressive ability to hit for both power and average, and his outfield range and throwing arm were among the best in the organization.”

Q: Charlie Peete’s manager at Omaha in 1955 and 1956 was Johnny Keane. Keane later was an influential mentor for Bob Gibson. Was Keane a similar mentor to Peete?

A. “Absolutely. In a questionnaire he completed in 1956, Peete specifically listed Johnny Keane as one of his top influences in baseball and he flourished tremendously under Keane’s tutelage in 1955-56. Keane, who once compared Peete to Hack Wilson, worked closely with him on his batting stance and helped him to greatly improve his power numbers.”

Q: Tom Alston, the first black to play for the Cardinals, was a teammate of Charlie Peete at Omaha. Any insights on how they got along?

A: “Peete and Alston seemed to have a strong relationship with each other, and as two of the trailblazing players in the Cardinals minor-league system, their careers were wholly intertwined in the mid-1950s. At Omaha, they were the first two black players to break the professional baseball color barrier in that city, which at the time still had many segregated institutions such as the municipal fire department. Although they never did play together in St. Louis, Peete and Alston both helped to change public perceptions at a time when the American civil rights movement was quickly accelerating.”

Q: Jackie Robinson’s last season in the majors was Charlie Peete’s first and only season in the majors. The Cardinals played the Dodgers in St. Louis soon after Peete got called up in July 1956 and again a month later. Any indication of interaction between Robinson and Peete?

A: “Peete and Robinson appeared briefly on the same field at Busch Stadium on July 22, 1956, when an aging Robinson pinch-hit for the Dodgers while Peete played center field as a defensive replacement in the top of the ninth. It was a remarkable moment for Peete, who in 1949 had tried out unsuccessfully for the Dodgers organization in his home state of Virginia and undoubtedly drew inspiration from Robinson’s entrance into the majors in 1947. Although it is not known whether Peete met Robinson on that day in 1956, he certainly drew Robinson’s attention by recording two outfield assists, including a double play he completed with Stan Musial at first base.”

Q: The Cardinals were late to integrate. Do you think Charlie Peete was comfortable being with the franchise? How was he treated?

A: “It’s difficult to say. Publicly, Peete said he valued his time with the big-league club in St. Louis, and the organization had nothing but praise for him as a player. His teammates also recalled very fond memories of him. However, the experience for Peete must have been extremely isolating, given that he was one of only a handful of black players in the organization at the time and the only black player on the major-league squad during that portion of the 1956 season. That was a hard time for any black player anywhere in baseball. When Peete played in Omaha, he could not even bring his family to live with him because the housing market was so deeply segregated. Also, as you mentioned, the Cardinals had resisted integration in the late 1940s and early 1950s and drew significant criticism from civil rights leaders in St. Louis because of that decision. That all changed when Anheuser-Busch and Gussie Busch took ownership of the franchise in 1953 and immediately took steps to integrate the organization. Despite Busch’s more tolerant and forward-thinking stance, it still took some time for the Cardinals to shake their negative perception _ which certainly impacted Peete. For example, after Peete’s demotion from St. Louis in August 1956, one of the city’s leading African American newspapers, the Argus, questioned why he had been sent back to the minors so quickly and felt the Cardinals were still applying unfair and unrealistic standards to black players.”

Q. What kind of teammate was Stan Musial to Charlie Peete?

A. “Peete adored Musial. When asked, ‘Who is the greatest player you have ever seen?’ Peete listed Musial because he ‘was a real ballplayer all around.’ “

Q. In 1957, following Charlie Peete’s death, the Cardinals shifted third baseman Ken Boyer to center field. Do you think if he had lived that Peete would have been the center fielder for the 1957 Cardinals?

A. “Although there are no guarantees, I do believe Peete would have started in center field for the Cardinals in 1957. In the months after his death, the Cardinals struggled to find another candidate for the job and ended up making the emergency decision to shift Boyer to center _ something I don’t think they would have needed to do if they still had Peete. I think Peete had clearly shown during his 23-game trial in 1956 that he could play defense at an elite major-league level, given his perfect fielding percentage and several dazzling plays in the outfield. Peete’s .192 batting average with the Cardinals in 1956 was not good, but as the reigning Class AAA batting champion there wasn’t much doubt in the organization that he would hit eventually.”

Q. Do the Cardinals still trade for Curt Flood in December 1957 if Charlie Peete was on the team?

A. “This is a fascinating question. Bing Devine’s first trade as general manager was the one that brought Flood over from Cincinnati at the winter meetings that year. I can see a scenario where Devine, satisfied with Peete as his center fielder, opts not to trade for Flood. In that scenario, does Peete become the center fielder for the World Series teams of the sixties? Does Flood, having never been traded to St. Louis in the first place, ever challenge the reserve clause and take his case to the Supreme Court? The whole history of major-league labor relations might have been impacted. However, I still think it’s possible Devine might have traded for Flood anyway in December 1957, even if he had Peete on the roster. Flood had played infield during his brief time in the majors with Cincinnati and Devine seemed to like his overall skillset as a position player, not solely as a center fielder. (It was manager Fred Hutchinson who came up with the idea of putting Flood in the outfield.) It’s possible Peete and Flood could have co-existed together for the next decade.”

Q. Anything else you’d like to tell our readers about the book and why they should buy it?

A. “Despite the tragic ending, I hope readers will walk away from the book with a better appreciation for Charlie Peete’s remarkable life and accomplishments. This was someone who grew up in segregated Virginia and began his professional career in the Negro Leagues, at a time when opportunities for black baseball players were still extremely limited. Over the course of the 1950s, Peete played an important role in the integration of both the minor leagues and the major leagues, and he bridged a gap in Cardinals history that laid the groundwork for some truly historic teams of the 1960s. Charlie Peete is a name that Cardinals fans should know and remember.”