It’s mid-winter. Let’s spitball a bit. Have a little fun.

Authors note: No doubt you’ve read about the devastation in Pacific Palisades, CA. I was woken up late Tuesday night with orders to deploy immediately. I expect to be gone a couple of weeks. There will still be content (ie. see below), but I won’t likely be able to engage much in the comments, which is half the fun. It’s nothing personal, and I will catch up in February. Such is the life of being packed and ready to go on a moment’s notice.

We are in the deep-freeze portion of the Hot Stove League. Winter is upon us. The GM meetings have come and gone, and we are in the rocking chair of time between Christmas (my favorite holiday) and the day Pitchers and Catchers Report (my favorite non-holiday). I find myself akin to the Roman god Janus. One face looking back at the past – in my case wondering what happened and how it can be corrected. Another face looking forward to the future – full of hope and adventure.

In the doldrums between those two calendar points and without any real baseball games to discuss, I’m searching through my list of potential topics to tease apart, and I’ve landed on this. A favorite idea of the boards – the 6-man rotation. What would a 6-man rotation look like? Today, I’d like to take a look, as in, how would it work logistically. This started out as a total spit-ball approach, although I think some of the data is a slight improvement on spitball.

NOTE: This article is going to focus on logistics – people, innings, roster spots. I won’t get into the quality aspect of this too much. There would be a WAR impact, for sure, but I more focus on — could this be done logistically?

Why a 6-man rotation is considered

First, I’ll clear away the obvious performance hit … by going with a 6-man rotation, a team gives up ~5 starts from each of its top 5 starters and gives them to their (ostensibly) 6th best starter, which is probably more an amalgam of young AAA arms than a single person.

The pay-off is arguably in pitcher health. We see this anecdotally when a team goes long stretches without a day off, and pitcher quality recedes some (do I have to quantify this or can the readers stipulate to this?) and guys end up needing to skip a start or be pushed back a few days to allow themselves enough rest. Another anecdotal support for this is that teams now regularly keep the 5th starter on schedule even when there are days off in the schedule, mostly to give guys “the extra day”. The rhetorical question becomes – why not institutionalize these practices and avoid all the chaos of jumbled rotation plans and bullpen games to achieve the same result?

Let’s assume two things then – there is a performance hit but there is a potential health payoff, and a team might view it as a worthy payoff, particularly in the latter stages of a season.

I will add to this that it appears the Dodgers plan to at least start the season with a 6-man rotation. They have 3 guys coming off surgery and need to manage innings and a 4th guy (Yamamoto) that is accustomed to working once a week. So apparently at least one team doesn’t view this as crazy. And now I read the Mets are heading the same direction. Follow the money, I guess. Let’s look.

How would it work? Or could it work?

Let’s start with those pesky roster rules … a team can carry 13 pitchers. Almost all (if not all) teams carry 5 starters and 8 relievers, 1 or 2 of which operate as “swingman”, “opener” or “bulk inning” guys.

Teams need these guys because there are unscheduled, unanticipated blips that arise during the season that require someone to carry bulk innings on short notice. These are often more experienced pitchers, more accustomed to the rigors of MLB scheduling and not as likely to get wigged-out or be unprepared when the moment presents itself. Cal Eldred is my favorite proxy for this kind of pitcher. I don’t think the need for this pitcher changes much with a 6-man rotation. Someone will throw a shoe, or a game will be suspended, a rain out that gets re-scheduled for tomorrow, a long rain delay in the 2nd inning that sidelines your starter, but not the innings he would have pitched. This will happen no matter how long your rotation is, 5-man or 6. And teams will need a guy.

Other than those 1-2 bulk guys, the rest of the bullpen breaks down by role – closer, high leverage guys, chase guys. As we saw in 2024, if you play a lot of close games, your closer and high leverage guys get taxed pretty easily. As we spit-ball a 6-man rotation, we must also spit-ball a shortened bullpen rotation. Within the 13-man rules, to carry a 6-man rotation you would be, by definition, shortening your bullpen rotation by 1 arm. Which one? Probably not the closer.

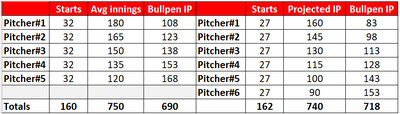

Let’s look at it from a starts and innings standpoint. Let’s start with assuming good health and stable performance from the rotation to solve for the simplest form of this problem. If you can’t solve for this, you probably can’t do it. We’ll compare innings pitched (IP) expected from each member of the rotation, using somewhat traditional expectations of #1 through #5 starters (180 inning from the #1, declining down through #5). You see this below on the left side of the sheet, with a 5-man rotation, with declining IP per rotation spot.

Note: I used modelled numbers here to follow the good health assumption. Actual experience in terms of league averages per rotation spot is shown in the second chart below.

The perfect model world – assumes good health and stable performance (ie. won’t happen)

In this overly simplified, overly optimistic world view, a 5-man rotation carries all but two of the starts throughout the season. Note that this really isn’t 5 pitchers, it’s 5 rotation spots often filled by more like 6-8 guys. The opener/bulk innings guys will carry the 2 extra starts, plus any aborted starts by 1-5, plus anything like suspended games carried over to the next day. We’ve seen how challenging it can be to piece together a rotation to fit this model 5-man rotation. This model places a 690-inning load on the 8-man bullpen “rotation”, which again isn’t 8 guys, but more like 10-12 guys filling 8 roles. That means an average of 86 IP per bullpen spot. Teams seem to like to stay in the 60-70 range per reliever, thus the need for 10-12 guys to carry this load.

On the right side of this chart, we carry forward the good health scenario but expand for a 6th spot in the starting rotation. I followed “traditional” assumptions for innings per start. The net reduction in IP is the result of only making 27 starts instead of 32. I did have to make up assumptions for spot#6 since there is no apparent historical data to draw from here but followed the decline pattern evident in the first 5 spots. I did assume that teams might see a modest increase in innings per start in a 6-man rotation, as manager might be more inclined to let a starter go a bit farther given an extra guaranteed day of rest. All these numbers assume 9 inning games all season to make the math easy. Any less (such as losing a road game means only 8 IP) will almost completely reduce the burden on the bullpen, not the starters. I estimate this impact to be ~25 innings (assumes 35 road losses that reduce load but 10 extra-inning games that add load). I don’t factor that into the numbers you see on the sheet because this impact is even across 5- and 6-man scenarios.

In this perfect world/will never happen view, a 6-man rotation would increase the load on the bullpen by ~30 innings over the season. Agreed this appears as a modest amount, but remember we are spreading these innings across 1 less reliever (7 instead of 8), so the relievers workload increases quite a bit more, from 86 to 102 IP per year (per bullpen slot, but not likely per pitcher). Their downtime would decrease, as well, as relievers tend to pitch shorter outings but more frequently than starters. I’d suggest this approach simply moves the health risk from the rotation to the bullpen. A second aspect of this would be that you’d likely see a team cycle more arms through AAA, essentially pushing those extra 30 innings onto the AAA staff. Like the rotation, you will see some performance impact as your #9 bullpen guy carries more innings in a 6-man rotation view.

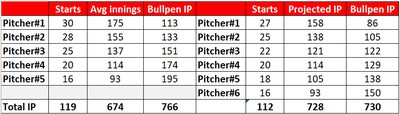

Let’s add some reality to this model and see

On the left side of the model, I replace the 5 starters @ 32 starts each with league average data for the top 5 starters for 2001-2024, both in terms of games started (GS) and innings pitched (IP). Notice that in this more realistic view, managers will have to find a way to plug in a starter for ~40 games per season. Openers/bulk inning guys/AAA guys cycled in/short rest, whatever. The actual burden that falls on the bullpen is more like 766 innings, spread over 8 bullpen slots, not the 690 modeled above.

On the right side of the model, I allocate the “traditional” assumptions to a 27-start scenario, with assumed (made up) number for spot#6. I did put my finger on the scale a bit here, by assuming that a team wouldn’t consider a 6-man rotation unless they had more capable people but probably not topflight starters. In this scenario, I even out the IP a bit, reflecting a bit less quality at the top of the rotation, but more even quality throughout. I adjust # of starts to league average, with an estimate on starter#6 based on observed trends. One might view the right side of this chart as looking a bit like what the 2024 Cardinal rotation would have looked like with 6 starters.

This is perhaps a more realistic scenario. Interestingly, the bullpen load drops by 36 innings, although the IP per reliever would rise a bit, since again, we are spreading 730 innings over 7 relief spots, not 766 over 8 spots. But not as drastic a bullpen workload increase as the theoretical model for sure, by adding a 6th starter.

Notice the starts. With a 5-man rotation, the “average” MLB team has to cover 43 starts a season outside of their set 5-man rotation. Due to injury, non-performance, scheduling quirks, whatever. A six-man rotation likely increases the number of starts from outside the rotation but also increases the number of innings you get from INSIDE the rotation. This is an interesting quirk. It almost becomes a strategy to concentrate more innings in your top 6 starters. Interesting.

The challenges of a 6-man rotation

26-man Roster management. Because the active roster rules on number of pitchers are inflexible, a team would have to put an emphasis on having arms that have options, so they can cycle guys in and out to manage individual workloads.

Option limits. Not only do the roster limits on pitchers matter (13), but teams can only option a guy 5 times in a season, so this is not an unending supply chain. I could see a reliever being swapped out bi-weekly in such a scenario. That is ~13 options. That is a lot of arms. And that is before injuries or non-performance force more moves.

Overall bullpen management. One less guy in the bullpen likely means more appearances, or at least more consecutive day appearance by relievers throughout the season.

Payroll. Here is a reality. One more starter costs more than one less reliever saves. Bulk innings get expensive quick. To be sure, a mid-range starter like Gibson at, say, $11m/yr could be a guy that could allow the 2025 team to extend to a 6-man rotation. But that is almost all a payroll adder.

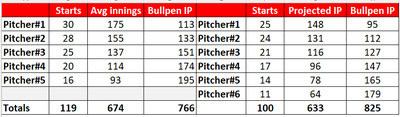

Uncontrollables. A six-man model is very dependent on good depth in your pitching staff. Once you start out a season with this model, the inevitable injury and performance risks will appear, and the model itself may break down as the depth erodes. If the model breaks down, then predictability and continuity go with it and that usually means poor outcomes for a pitching staff. If there is no health benefit, and 6-man rotations have the same reliably as 5-man rotations, here is what that looks like on the six-man side (right side of chart below). These numbers are league-wide average over the last 4 seasons (more on that in a bit), with some guessing on pitcher#6 based on observed trend.

This scenario gets kind of ugly. You get less starts, less innings and more load on a shorter bullpen. Yikes! Realistically, you wouldn’t go here if you didn’t think you had 6 or 7 guys you were confident could make at least 16 starts.

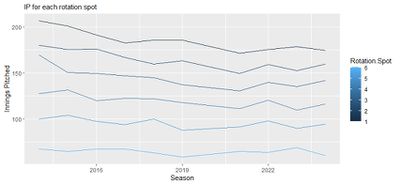

Some observations about the historical data used

For those of you wondering why I took league averages over the last 4 seasons, I actually went further back. As expected, I observed the long-term trend down in starter IP, but I also noticed that this appears to have stabilized since 2021. See below for the visual:

The opportunities of a 6-man rotation

While a 6-man rotation might not be a great idea for a team top-heavy in rotation talent, a team deep in mid-range starters, good bullpen depth and good AAA arms with options could use it to some advantage.

7-day work schedule. MLB has gradually modified its scheduling, extending the season by a few days, introducing a couple extra off-days and reducing in-division games. The result is that something like 60% of the calendar weeks in the season include a day off. Most of these are aligned such that there are 6 games between days off (often two 3-game series, followed by a travel day). A six man rotation would fit that schedule quite well. For those weeks, you’d basically be pitching guys once a week, on a regular schedule. Pitchers, if nothing else, like a routine. If they wanted to be hyper-aggressive about keeping such a schedule, I count 5 days in the season where a swing starter/opener (not the #6, but the bulk innings reliever) could be used to keep everyone on a pure 6 day pitching plus 1 day off rotation (you’ll see these as the 5 stretches that are 13 games consecutive and a swing starter in the middle game would look to the rest of the rotation just like a day off). In practice, this takes a 5-man rotation with guys frequently pitching every 5th day and makes it a 6-man rotation with guys pitching every 7th day all the time. I wonder what the health impact of the predictable extra 2 days would be. This catches my eye.

Innings management. The Cardinals (and Dodgers) have a slew of pitchers who aren’t going to even pitch 150 innings this year, so inning management is a major concern and one that a 6-man rotation can help with. Note that the 6-man model assumes no pitcher will be tasked with greater than 150 innings. This list of guys needing innings managed includes: Hence, Roby, Matz. Probably Pallante and McGreevy, too. With a 6-man MLB rotation, they could match up work schedules with Memphis and cycle guys in and out without disrupting schedules. For example, if Hence pitches every Tuesday in the minors, he can come up and make a Tuesday start at the MLB level (if that is what is needed), return to the minors and make an abbreviated start the next Tuesday (to manage work load) and then he could pitch at either level the following Tuesday as the 10-day option period would have expired.

40-man Roster Management. Teams often have 22-23 pitchers on their 40-man roster. They carry 13 of them on the active roster at any one time, leaving 9-10 in the minors. Most, if not all, of those guys see time in the majors. Realistically, with a 5-man rotation it is already a pretty good challenge to fill all the starts, and manage the inning loads with 13 pitchers when you only have 9-10 guys on the 40-man that can step in to fill in for non-performance, injuries, double headers, etc. A six-man rotation would concentrate some of the innings gap into one or two guys on a schedule, instead of having it be more random/piece together. A side observation is that as MLB has introduced 26-man rosters with pitching limitations, expanding the 40-man roster seems like a logical next step.

Piggyback (redefined) – In a prior era, minor league teams would piggyback starters in a game before going into traditional relief roles. This allowed them to manage inning loads for young pitchers and effectively have 10 starters getting exposure, not the traditional five. Results were…mixed. The 6-man rotation might actually result in a redefined piggy-back where AAA pitchers mirror (in reverse) the major league rotation.

For instance, start with an assumed MLB 6-man rotation of Gray, Fedde, Pallante, Mikolas, Matz, McGreevy. If you thought Q. Matthews would likely be first up to fill an MLB rotation spot, you’d start him at AAA same day as the #6 starter of the major league team (the spot most likely to require filling). Likewise, if you thought you’d only spot T. Hence into the MLB rotation a few times for exposure, he’d start the same day S. Gray would start (the spot you would expect to have the least problems with). And so on. Because the 6-man rotation would effectively put the major league rotation on the same rotation as the AAA schedule (6 games, 1 day off), this could happen in a managed way. Whenever a guy goes on the IL or under-performance or innings management results in an option, the matching piggyback would come up and take that start right on schedule. No shuffling, no short rest starts. Plus, the manager doesn’t have to “hold back” a bullpen pitcher on the chance he might need to “open” later in a series, creating a more flexible bullpen.

Is it practical?

Remember here, I am spit-balling. Practicality isn’t a requirement. Not today.

I see two scenarios where a 6-man rotation might be useful. One, with a team like the Cardinals that had a bunch of mid-tier starters and two, a team that wants to work in a bunch of young (or recovering) pitchers but needs to manage innings. One could argue that the grey-beard rotation of 2024 could have benefitted from a 6-man rotation. Having that 6th starter who can do it would have helped, though (say, a healthy Steven Matz, in 2024). In 2025, a Kyle Gibson might go a long way toward making this workable. Remember … spit-balling.

In all scenarios, such a team would need to be loaded up with fresh arms with lots of minor league options left. By definition, that means young guys, who are most often the least flexible and least adaptive to the kind of role change/schedule yo-yos that could come with such a setup.

Overall, for a serious contender that needs to maximize its top-flight pitching at the top, I’d say this isn’t a good path to follow. For the Cardinals in 2025, where winning isn’t everything, and with lots of young arms that need both exposure and innings management, this might be a play.

Thoughts?