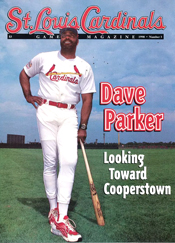

A trade of Dave Parker for George Hendrick during their playing days would have been a headliner. That didn’t happen, but this did: Parker and Hendrick essentially were swapped for one another as coaches.

After coaching for the Angels in 1997, Parker became Cardinals hitting coach. He replaced Hendrick, who took the Angels coaching job Parker vacated.

After coaching for the Angels in 1997, Parker became Cardinals hitting coach. He replaced Hendrick, who took the Angels coaching job Parker vacated.

Parker’s stint with St. Louis lasted one season. Though the Cardinals had the highest home run total in the National League with Parker as hitting coach in 1998, he wasn’t brought back. Manager Tony La Russa said Parker wasn’t dedicated to the job because he was spending time on the Popeyes fried chicken restaurant he owned in Cincinnati.

A success in the restaurant business, Parker capped his athletic career on Dec. 8, 2024, when a committee elected him to the Baseball Hall of Fame for his playing feats. The 16-member committee included former Cardinals Lee Smith, Ozzie Smith and Joe Torre, and Dick Kaegel, a former St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter.

Show time

A left-handed batter and right fielder, Parker hit for average and power, produced runs and played with flair for the Pirates (1973-83), Reds (1984-87), Athletics (1988-89), Brewers (1990), Angels (1991) and Blue Jays (1991).

Nicknamed “Cobra” for the way he waved the bat before uncoiling with a quick swing, Parker was the National League batting champion in 1977 (.338) and 1978 (.334). He led the league in hits (215) and doubles (44) in 1977 and was the NL Most Valuable Player Award recipient in 1978.

A three-time Gold Glove Award winner with a powerful throwing arm, Parker played for two World Series champions (1979 Pirates and 1989 Athletics) and the 1988 pennant-winning A’s.

A career .290 hitter, he batted .314 versus the Cardinals. He totaled 2,712 hits and 1,493 RBI in 19 seasons in the majors.

(Parker respected fellow mashers. In his memoir, Keith Hernandez recalled, “Dave Parker, one of the most talented players I’ve ever seen, came strolling up to Ted Simmons and me after witnessing a round of batting practice in Pittsburgh and exclaimed, ‘You two are the hittingest white boys I’ve ever seen.’ Simmons laughed and I loved it: I’m Keith Hernandez, Hittingest White Boy.”)

Parker made his mark in other ways, too. He was one of the first ballplayers to wear an earring on the field (a diamond with a dangly cross) and one of the first to perform a showboating home run trot.

(Parker developed variations of his trot. He’d shoot at a base with his fingers as he neared it, according to the Post-Dispatch. Or, he’d trudge toward first “like a fat man up Heartbreak Hill,” Stan Sutton of the Louisville Courier-Journal noted, and slowly circle the bases. “I’ve hit over 300 of these,” Parker told the Los Angeles Times in 1989. “I deserve the opportunity to run them out any way I want.”)

Testifying in a 1985 federal drug trial regarding cocaine distribution among ballplayers, Parker detailed his cocaine use from 1976 to 1982, and identified colleagues who used the drug, in exchange for immunity.

Business decisions

In 1992, Parker sought to own a business in Cincinnati, where he grew up and still resided. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, “A broker suggested Parker open a Burger King restaurant. Before the deal closed, the broker instead directed Parker to Popeyes because there were 18 Burger Kings in the region and one Popeyes.”

Parker and his wife, Kellye, bought a Popeyes on busy Reading Road in Roselawn, a Cincinnati neighborhood. According to the Enquirer, Parker could be found in the dining area or in the kitchen “where he regularly preps food or helps staff.”

“We call our Roselawn restaurant the colonel-killer,” Parker told the newspaper. “I think there are something like three KFCs that have gone out of business on Reading Road since we’ve been there.”

During the summer of 1996, Parker met with Terry Collins, then manager of the Astros, who were in town for a series against the Reds. Parker and Collins were teammates in the minors. Parker told him he was interested in getting back into baseball, the Los Angeles Times reported.

In November 1996, a month after the Astros fired him, Collins was hired to manage the Angels. He retained Rod Carew as hitting coach, but added Parker to the staff. Though Parker had no coaching experience, “He bring tremendous credibility,” Collins told the Times. “He knows how to win, what it takes to win. He brings the presence and knowledge of what it takes to be successful.”

Parker, 45, said to the Times, “I know I have to display clubhouse leadership. That was the understanding when I took the job.”

Or, as the Times put it, Parker was enlisted “to help give the Angels a long-needed kick in the rear end.”

Another motivation for Parker was his appearance on the Baseball Hall of Fame ballot for the first time in 1997. As he told the Post-Dispatch, “With the Hall of Fame voting, I came back to baseball just to be more visible.”

Parker was assigned to be the first base coach and instruct the outfielders, a group that included Jim Edmonds.

Here’s the plan

As a player, George Hendrick totaled 1,980 hits, including 267 home runs, and never struck out as many as 90 times in a season. In his two years as Cardinals hitting coach, the team ranked a lackluster seventh in the National League in runs scored in 1996 and 11th in 1997. Worse, the 1997 Cardinals struck out more than any other team in the league.

The combination of the strikeouts and the hitters’ lack of application frustrated Hendrick. Though manager Tony La Russa was interested in having him return in 1998, Hendrick opted to leave, the Post-Dispatch reported.

In October 1997, Parker, who played for La Russa when he managed the Athletics, was hired to replace Hendrick. “Parker will be entrusted with correcting the Cardinals’ strikeout total,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

Parker told the paper, “When I played for Tony, I taught Jose Canseco a two-strike stance and he cut down on his strikeouts quite a bit (from 157 in 1987 to 128 in 1988). He also hit 17 home runs (from a total of 42) with his two-strike stance.”

By encouraging a batter with two strikes in the count to spread out his stance and cut down his swing, “You concentrate on just putting the ball in play,” Parker said to reporter Rick Hummel. “You look for the fastball and adjust to everything else.”

Working with a 1998 Cardinals lineup that included Ron Gant, Brian Jordan, Ray Lankford and Mark McGwire, Parker arranged contests during batting practice at spring training. According to the Post-Dispatch, “Coaches call out situations to the hitters and points are subtracted for bad execution, such as not moving a runner along. At the end of the competition, the losing side of hitters has to serve drinks and sandwiches.”

Parker told the newspaper, “You put it in their heads every day and eventually it gets there. You get a guy at third base with less than two outs, you don’t swing at a slider away … It’s constant repetition.”

One and done

Though the Cardinals still struck out a lot (1,179 times), they scored more runs in 1998 (810) than they did in 1997 (689).

Afterward, Parker told the Post-Dispatch, “If they want me back, I’d come back.” However, the Cardinals informed him he wasn’t wanted because his business interests interfered with his coaching duties.

“Coaching is a commitment,” La Russa told the Post-Dispatch. “I don’t know any coach who’s really outstanding that can have a conflict (of interest). The entrepreneur side of (Parker) prevented a total dedication to coaching … Coaching, if you do it right, consumes you. If you get into professional coaching and managing, if you have a business, you’d better find somebody to run it for you. He made a decision to divide his interests, and you can’t do that.”

Parker told the newspaper, “I really enjoy baseball, but I just don’t like being away from business … It’s tough being gone for eight months a year. My wife is working almost to death.”

Regarding his stay with St. Louis, he added, “If I had known it would have been so short, I never would have left the Angels.”

Mike Easler replaced Parker. Soon after, Mark McGwire sued People First Inc, distributor of a pain reliever, The Freedom Formula, saying the company falsely claimed he endorsed the product.

According to the Post-Dispatch, the lawsuit contended that “Dave Parker, who promoted The Freedom Formula, distributed the product to McGwire and several teammates (in 1998). Parker asked McGwire to pose for a photograph of him holding a bottle of The Freedom Formula. As a courtesy to Parker, McGwire posed for the picture but never consented to its use for any commercial purpose.”

(McGwire’s lawyer told the newspaper the dispute had nothing to do with Parker’s departure from the Cardinals. The suit was dropped when People First Inc. agreed to stop using McGwire’s likeness, the Post-Dispatch reported.)

Parker’s Popeyes restaurant continued to do well and he eventually opened a second one in Forest Park, a Cincinnati suburb.