Lou Brock had the legs; Jerry Grote had the arm. What sometimes made the difference in their showdowns was their heads.

During Brock’s prime years with the Cardinals, when he led the National League in stolen bases eight times, one of the most difficult catchers to steal against was Grote, who played for the Mets.

During Brock’s prime years with the Cardinals, when he led the National League in stolen bases eight times, one of the most difficult catchers to steal against was Grote, who played for the Mets.

“Grote has been hailed as the best defensive catcher in the game, equal to Johnny Bench and Carlton Fisk in mechanics but better at setting up hitters,” the New York Daily News noted in 1976.

According to the New York Times, Bench remarked, “If the Cincinnati Reds had Grote, I’d be playing third base.”

In 1966, when he led the NL in steals for the first time, Brock told Newsday that Grote “may be the toughest catcher in the league to steal against.”

To counter Grote’s quick release and strong throws, Brock used mind games in a bid to gain the upper hand.

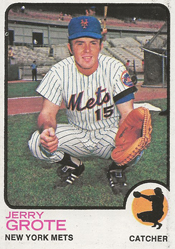

A two-time all-star who played in four World Series (two each with the Mets and Dodgers), Grote was 81 when he died on April 7, 2024.

Texas roots

After a year at Trinity University in his hometown of San Antonio, Grote, 20, played his first season of professional baseball in 1963 with the San Antonio Bullets, a Houston Colt .45s farm club. There, he was tutored by player-coach Clint “Scrap Iron” Courtney, the former St. Louis Browns catcher.

Called up to Houston in September 1963, Grote stuck with the big-league club in 1964, but “I caught knuckleballs from Ken Johnson and (Hal) Skinny Brown and I was fortunate to just hang on,” he told Newsday.

Prone to taking big swings, the rookie also struggled at the plate, batting .181 in 1964 and totaling more strikeouts (75) than hits (54). In a game at St. Louis, he struck out four times. Boxscore

After the season, the Mets offered outfielder Joe Christopher and others to Houston for catcher John Bateman. Houston instead proposed sending them Grote, but the Mets said no, according to Dick Young of the New York Daily News.

Grote spent the 1965 season in the minors. Afterward, when the Mets again asked for Bateman, Houston still offered Grote, but this time the Mets said yes. On Oct. 19, 1965, Grote was traded to the Mets for pitcher Tom Parsons and cash.

Transformer man

Though he didn’t hit much, Grote impressed with his catching skills and became the Mets’ starter. “He’s a catcher a team can win with,” Mets coach Whitey Herzog told Newsday in 1966.

A year later, in September 1967, when asked to rate the catcher who was the toughest to steal bases against, Lou Brock replied to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “For quickness in getting rid of the ball and accuracy, I have to pick Grote.”

Grote also had a reputation for constantly complaining to umpires about their calls. When Gil Hodges became Mets manager in 1968, he ordered Grote to stop bickering. According to Dick Young in the New York Daily News, Hodges said to Grote, “There is a time to argue. If you think he has blown one, tell him. Then get it over with. You have to be more concerned with the course of a game. You have to think about situations. There’s more to catching than putting down one finger, and here comes the fastball.”

Hodges also worked with Grote to improve his hitting _ and the results were immediate. After batting .195 in 1967, Grote hit .282 in Hodges’ first season as Mets manager in 1968. As Dick Young noted, “He cut down on his swing, and went to the opposite field with the pitch away from him.”

As a result, Grote was the National League starting catcher _ ahead of Johnny Bench, Tim McCarver and Joe Torre _ in the 1968 All-Star Game.

Psychological edge

With Grote catching pitchers such as Tom Seaver, Nolan Ryan and Jerry Koosman, the Mets became World Series champions in 1969. Grote threw out 56 percent (40 of 71) of the runners attempting to steal against him that season, but Brock figured out a way to foil him.

In 1968, when the Cardinals won their second consecutive National League pennant, Brock was successful on 84 percent of his steal attempts but was safe on just three of six tries against the Mets. A year later, Brock was perfect in seven steal tries versus the Mets.

“I used to have trouble stealing when Grote was catching,” Brock told Newsday. “I think he had caught me about six of 10 times. Then one day I passed him after a game and I hollered, ‘Grote!’ He didn’t appear to hear me. So I hollered louder, ‘Grote!’ He still didn’t answer me and I yelled his name a third time louder than the first two. His neck turned three shades of pink and I realized then that he didn’t like to be yelled at. So the next time I got on first in a game against the Mets, I hollered his name and he hollered back at me. Ever since then, I’ve had about 80 percent success stealing when Grote is catching.”

Once Brock saw he could light Grote’s short fuse, he never let up.

“One of the delights of a visit of the Cardinals to Shea Stadium when the Mets were an attraction was Brock’s confrontation with Jerry Grote, who had a gun for a catcher’s arm and a disposition to match,” Newsday’s Steve Jacobson noted. “Brock would take his lead off first base and scream his taunt: ‘Yaaah, Grote! I’m going, Grote!’ The challenge was thrown.”

In 1970, when asked again to rank the toughest catchers to steal against, Brock put Manny Sanguillen and Johnny Bench ahead of Grote. Brock claimed Grote was inching toward the plate to shorten his throws and compensate for diminishing arm strength. “Grote keeps moving in all the time.” Brock told the Post-Dispatch. “The way Grote’s always moving toward the pitcher, I’m surprised he hasn’t been hurt by a backswing.”

The Mets won their second National League pennant in 1973 and contended with the defending champion Athletics before losing in Game 7 of the World Series.

In a testament to how valuable he was to the team, Grote caught every inning of the Mets’ National League Championship Series and World Series games in 1969 and 1973. “He’s the best catcher a pitcher could want to throw to,” Tom Seaver told the New York Times.

Mellow my mind

Grote had a reputation for snapping at reporters and official scorers and for being gruff with teammates. George Vecsey of the New York Times described him as “the resident grump” of the Mets clubhouse. Milton Richman of United Press International wrote, “He was one of those sullen, unsociable citizens who preferred his own private company and wouldn’t hesitate to let you know it.”

Mets first baseman Ed Kranepool told the wire service, “He and I have always gotten along fine, but I know a lot of people sort of felt he was cold and distant.”

Pitcher Jon Matlack said to the New York Times, “I was scared to death that I’d bounce a curveball into the dirt and get him mad. You worried about him more than the hitter. One day I told him: ‘Look, I’ll pitch my game and you catch the ball. OK?’ After that, we got to be friends and roommates, and I began to see the many sides of Jerry Grote.”

In the mid 1970s, Grote joined teammate Del Unser in the daily practice of Transcendental Meditation. “I found it really relaxes me, gets me ready for the game and conserves energy,” Grote said to the New York Daily News.

Matlack told the New York Times, “On the field, he was all aggression. Off the field, he was many men: tender to his family, generous to his friends.”

Though not considered a slugger, Grote twice hit home runs to beat the Cardinals. A two-run shot against Bob Gibson provided the winning runs in a 1974 game. (For his career, Grote batted .139 versus Gibson and struck out 20 times.) Boxscore

In 1976, Grote’s ninth-inning homer against Pete Falcone gave Seaver and the Mets a 5-4 win. Boxscore

After Grote beat former teammate Tug McGraw with a ninth-inning home run at Philadelphia, the reliever told the New York Times, “Grote’s been catching me for 10 years and now he knows my mind better than I do.” Boxscore

The pitcher Grote hit best was Steve Carlton. In 85 plate appearances against the future Hall of Famer, Grote had a .405 on-base percentage.

Traded to the Dodgers, Grote appeared in the World Series with them in 1977 and 1978 as a backup to Steve Yeager. (Yeager told the Dayton Journal Herald, “There are only three real good, all-around catchers in the National League _ Johnny Bench, Jerry Grote and me.”

In 1981, when Grote, 38, played his final big-league season, he produced seven RBI for the Royals in a game against the Mariners. “The older the violin, the sweeter the music,” he told the Associated Press. Boxscore