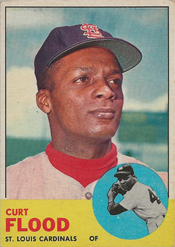

Early in his big-league playing career, Curt Flood had a tendency to try hitting home runs, which wasn’t a good idea for someone his size.

In 1958, his first season with the Cardinals, Flood, 20, clouted 10 homers. Those are the most home runs of any Cardinals player 20 or younger, according to researcher Tom Orf.

In 1958, his first season with the Cardinals, Flood, 20, clouted 10 homers. Those are the most home runs of any Cardinals player 20 or younger, according to researcher Tom Orf.

The long balls caused Flood to overswing. It wasn’t until a teammate helped him kick the habit that Flood became one of the National League’s top hitters.

Big talent

As a youth in Oakland, Flood was a standout art student and high school baseball player. A mentor, George Powles, also coached him with an American Legion team and in the semipro Alameda Winter League.

“This kid can do everything,” Powles told the Oakland Tribune. “He can run, throw, field and hit a long ball. He is smart and has great desire to get ahead.”

Big-league scouts took a look, but most determined Flood was too small to reach the majors.

In his autobiography “The Way It Is,” Flood recalled, “One day George Powles sat me down for a talk. He told me I had the ability to become a professional, but that I should prepare for difficulties and disappointments. He pointed out I weighed barely 140 pounds (and) was not more than five feet, seven inches tall … Small men seldom got very far in baseball.”

Reds scout Bobby Mattick, a former big-league shortstop, took a chance on Flood. In January 1956, after Flood turned 18 and graduated from high school, he signed with the Reds for $4,000.

Down in Dixie

Assigned to a farm club in High Point, N.C., a furniture factory town, Flood experienced racist teammates and fans.

“Most of the players on my team were offended by my presence and would not even talk to me when we were off the field,” Flood said in his autobiography. “The few who were more enlightened were afraid to antagonize the others.

“During the early weeks of the season, I’d break into tears as soon as I reached the safety of my room … I wanted to be free of these animals whose 50-cent bleacher ticket was a license to curse my color and deny my humanity. I wanted to be free of the imbeciles on the ball team.”

Flood’s pride kept him from quitting and he answered the bigots by performing better than any other player in the Carolina League. “I ran myself down to less than 135 pounds in the blistering heat,” he said in his book. “I completely wiped out that peckerwood league.”

The 18-year-old produced an on-base percentage of .448 (190 hits, 102 walks). He scored 133 runs, drove in 128 and slugged 29 home runs.

Called up to the Reds in September 1956, Flood made his big-league debut at St. Louis as a pinch-runner for catcher Smoky Burgess. Boxscore

The next season became another ordeal when the Reds returned Flood, 19, to the segregated South at Savannah, Ga. Adding to the pressure was the Reds’ decision to shift Flood from outfield to third base. One of his infield teammates was shortstop Leo Cardenas, a dark-skinned Cuban.

“Georgia law forbade Cardenas and me to dress with the white players,” Flood said in his book. “A separate cubicle was constructed for us. Some of the players were decent enough to detest the arrangement. I particularly remember (outfielder) Buddy Gilbert (of Knoxville, Tenn.), who used to bring food to me and Leo in the bus so that we would not have to stand at the back doors of restaurants.”

A future seven-time Gold Glove Award winner as a National League outfielder, Flood made 41 errors at third base with Savannah, but produced a .388 on-base percentage (170 hits, 81 walks), 98 runs scored and 82 RBI.

Earning another promotion to the Reds in September 1957, Flood’s first hit in the majors was a home run at Cincinnati against Moe Drabowsky of the Cubs. It turned out to be Flood’s last game with the Reds. Boxscore

Good deal

At the 1957 baseball winter meetings in Colorado Springs, Cardinals general manager Bing Devine and manager Fred Hutchinson met until 3 a.m. with Reds general manager Gabe Paul and manager Birdie Tebbetts, trying to make a trade, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

After much give and take, the Reds proposed sending Flood and outfielder Joe Taylor to the Cardinals for pitchers Marty Kutyna, Willard Schmidt and Ted Wieand. Devine, in his first trade negotiations since replacing Frank Lane as general manager, “had some fear and trepidation” about doing the deal, he said in his autobiography “The Memoirs of Bing Devine.”

As Devine recalled in his book, Hutchinson said to him, “Awww, come on. I’ve heard about Curt Flood and his ability. Flood can run and throw. He could probably play the outfield. Let’s don’t worry about it.”

Bolstered by his manager, Devine made the trade, his first for the Cardinals.

(Concern of having an all-black outfield of Frank Robinson, Vada Pinson and Flood prompted the Reds to trade him, Flood said in his autobiography.)

Devine told the St. Louis newspapers that Flood had potential to become the Cardinals’ center fielder. “We’re counting on him for 1959, not next year,” Devine told the Globe-Democrat.

Cardinals calling

The Cardinals opened the 1958 season with Bobby Gene Smith in center and sent Flood to Omaha, but Smith didn’t hit (.200 in April) and Flood did (.340 in 15 games). On May 1, they switched roles, Flood joining the Cardinals and Smith going to Omaha.

(When the Cardinals sent Flood a ticket for a flight from Omaha, he was concerned how he would get his new Thunderbird automobile to St. Louis. Omaha general manager Bill Bergesch kindly offered to drive the car there for him and Flood accepted, according to Bergesch’s son, Robert. Not knowing anyone in St. Louis, Flood rented a room in a house called the Heritage Arms on the recommendation of pitcher Sam Jones. In the book “The Curt Flood Story,” author Stuart L. Weiss noted that when Bill Bergesch arrived in St. Louis with Flood’s car, he found Flood was residing in one of the city’s most notorious bordellos.)

Flood, 20, played his first game for the Cardinals on May 2, 1958, at St. Louis against the Reds. The center fielder had a double and was hit by a Brooks Lawrence pitch. Boxscore

His first home run for the Cardinals came on May 15 at St. Louis against the Giants’ 19-year-old left-hander, Mike McCormick. Flood belted a changeup into the bleachers just inside the left field foul line. He also singled to center and doubled to right, prompting the Globe-Democrat to declare, “Flood resembled a junior grade Rogers Hornsby with a surprising ability to hit to all fields.” Boxscore

Among Flood’s 10 homers in 1958 were solo shots against Warren Spahn and Sandy Koufax. Boxscore and Boxscore

The power impressed, especially on a club with one 20-homer hitter (Ken Boyer), but Flood’s .261 batting average didn’t (the Cardinals had hoped for .280) and he struck out 56 times, the most of any Cardinal.

“I had fallen into the disastrous habit of overswinging,” Flood said in his autobiography. “Worse, I had developed a hitch in my swing. When the pitcher released the ball, my bat was not ready because I was busy pulling it back in a kind of windup.”

Fixing flaws

In February 1959, Flood got married in Tijuana, Mexico, to Beverly Collins, “a petite, sophisticated teenager with two children,” according to “The Curt Flood Story.” They’d met during the summer at her parents’ St. Louis nightclub, The Talk of the Town.

Solly Hemus, who’d replaced Fred Hutchinson as Cardinals manager, wanted a center fielder who hit with power. Trying to deliver, Flood went into a deep slump in 1959 and entered July with a batting mark of .192 for the season. “I now became more worried about my swing and more receptive to help,” Flood recalled in his book.

According to Flood’s book, when he asked Stan Musial for advice, Musial said, “Well, you wait for a strike. Then you knock the shit out of it.”

Help came from another teammate, pinch-hitter George Crowe, 38. “George straightened me out,” Flood said in his autobiography. “He taught me to shorten my stride and my swing, to eliminate the hitch, to keep my head still and my stroke level. He not only told me what to do, but why to do it and how to do it. He worked with me by the hour.”

It took a while, but Flood finally found his groove. In 1961, he hit .322, the first of six .300 seasons for the 1960s Cardinals. Flood twice achieved 200 hits in a season and finished with 1,854 in the majors.

In 1968, he told the Associated Press, “It took me five years to learn I’m not a home run hitter, and that’s the hardest thing in the world for a baseball player to tell himself. It’s a blow to your ego. You have to tell yourself you’re not as big and strong as the next guy. It hits at your masculinity, your manhood.”

Of Flood’s 85 big-league home runs, the most (15) came against the Reds. Flood hit four homers versus Juan Marichal and two each against Don Drysdale, Ferguson Jenkins and Sandy Koufax.