For the 1953 St. Louis Browns, a downtrodden group accustomed to having the odds stacked against them, the numbers 14 and 18 added up to one in a million as they arrived in New York to play the Yankees.

Fourteen was the number of consecutive losses the Browns had suffered. Eighteen was how many the Yankees had won in a row. Recalling the team’s mindset entering the four-game series at home with the Browns, Mickey Mantle told “Voices From Cooperstown” author Anthony J. Connor, “We figured there’s at least four more wins.”

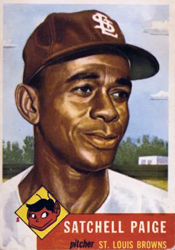

What the Yankees didn’t factor, though, was another number: 47. The oldest player in the majors, Browns pitcher Satchel Paige, turned 47 in 1953. At least that was his listed age. As the St. Louis Post-Dispatch suggested, Paige “is believed to be older than the American League,” which was formed in 1901.

Paige’s favorite number was zero. Those were the number of runs he allowed in securing the victory that ended the Browns’ skid and snapped the Yankees’ winning streak.

Together again

The story of Leroy “Satchel” Paige’s stint with St. Louis begins in July 1951. That was when Bill Veeck bought the Browns from Bill DeWitt Sr. and his brother, Charlie. A few days after Veeck closed the deal, he watched a dreary doubleheader in which Browns pitchers issued 15 walks to Philadelphia Athletics batters, losing both games. Boxscore and Boxscore

That’s when Veeck reached out to Paige, who was pitching for the Chicago American Giants of the Negro American League, and brought him back to the majors. “One thing about Satch is that he can get the ball over (the plate),” Veeck told the Post-Dispatch.

As owner of the Cleveland Indians, Veeck gave Paige his first shot at the big leagues, signing him in July 1948. Paige rewarded him, posting a 6-1 record and helping the Indians become World Series champions that year. After the following season, in 1949, Veeck sold the club and Paige was released by the new regime.

Senior league

Paige began pitching in baseball’s Negro League in 1927. He signed with the Browns on July 14, 1951, a week after he turned 45. Many suspected he was older than that. Even Veeck told the Post-Dispatch, “He’s at least 51.”

Trying to unravel the mystery of how ancient Paige was became baseball’s top parlor game.

After attempting to determine Paige’s true age, columnist Henry McLemore of the McNaught Syndicate informed readers, “I have come to the conclusion that Satchel was 10th off the Ark, and that while the waters were receding he practiced his curveballs.”

Noting that Paige is “the only baseball player in the world whose birthdays run backward instead of forward,” the Post-Dispatch concluded, “While Satch may be 50, his arm is only 25.”

After joining the 1951 Browns, Paige was invited to attend a gathering of 700 scientists that summer at the International Gerontological Congress at the Hotel Jefferson in St. Louis. Paige was a guest of the group’s president, Dr. E.V. Cowdry, professor of anatomy at Washington University school of medicine.

The “purpose of the congress is the discussion of aging, a subject close to Satch’s heart,” the Post-Dispatch reported. “Satch told the scientists he is still going strong because he works every day in the summer, hunts every day in the winter, eats lots of seafood, shuns beer, whiskey, chicken livers and lamb, and likes to sleep.” He added, “When I smoke, I don’t inhale _ just blow it out my nose.”

Mound magician

After making two starts for the 1951 Browns, Paige was moved to the bullpen, a role that better suited a pitcher of his advanced years. In 20 relief appearances, he totaled three wins and six saves using what the New York Times described as “an amazing assortment of trick deliveries” that included a hesitation pitch. According to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, the pitch got that name because when Paige threw it he went into a “big windup, stepped forward and stooped his body, but his arm continued in a wide arc” before he flipped the ball across the plate. “Damndest changeup pitch I ever saw,” Joe DiMaggio told the Times.

In a game against the Red Sox at Fenway Park, Paige got an 0-and-2 count on Ted Williams. On the next delivery, Paige went into a leisurely windup, and Williams moved forward in the batter’s box, expecting the hesitation pitch or something similar. Instead, Paige zipped a fastball, startling Williams, who swung late and missed for strike three.

Irate, Williams stomped to the dugout and “smashed his bat into pieces,” the Boston Globe reported. “He first whacked it against the railing of the runway leading to the dressing room. When that didn’t suffice, Williams flung the bat toward the rack. He still wasn’t satisfied, so he smashed it on the floor.”

During Ted’s tantrum, Paige was laughing on the mound, according to the Globe. He told the newspaper, “I’ve never seen anything like it in the big leagues. He was sore because I crossed him up.” Boxscore

For his career, Williams batted .222 (2 for 9) versus Paige. Both hits were singles. That was better than Joe DiMaggio did. The Yankee Clipper went hitless (with three strikeouts) in eight at-bats against Paige.

[In his induction speech at the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966, Williams said, “I hope Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson somehow will be inducted here as symbols of the great Negro (League) players who are not here because they were not given a chance.”]

Winners and losers

In 1952, Paige had 12 wins, 10 saves and a 3.07 ERA for the Browns. His last season with them was 1953.

The 1953 Browns lost nine in a row in May. Then came the 14-game skid in June. All 14 losses came at home. The Browns took a 19-38 record into the June 16 series opener against the Yankees at New York. Winners of 18 in a row, the Yankees were 41-11. Furthermore, their starting pitcher for the first game was Whitey Ford, who, in two seasons with them, was 16-0 as a starter.

A former Yankee, Duane Pillette, was matched against Ford that night. Pillette’s ERA for the season was 5.73.

What should have been a mismatch turned out to be a competitive contest. The Browns scored three runs against Ford, who was lifted after five innings. Pillette limited the Yankees to one run through seven.

In the eighth, after Billy Martin singled with one out, Pillette went to a 2-and-0 count on Joe Collins. Browns manager Marty Marion opted to lift Pillette for Paige.

(Perhaps looking to change the Browns’ luck, Marion, the former Cardinals shortstop, put himself in the starting lineup that night for the only time in 1953. Furthermore, he played third base for the first time in his career.)

Paige ambled from the bullpen to the mound. It took him about 10 minutes to stroll out there, according to the New York Daily News. As the Globe-Democrat noted, “His pants cuff was dragging but there was nothing wrong with the elastic in his arm.”

His first pitch to Collins was out of the strike zone, making the count 3-and-0. Then he retired him on a soft fly. After falling behind 3-and-0 to Irv Noren, Paige got him to pop out to the catcher.

With the Browns still holding a 3-1 lead, Mickey Mantle led off the bottom of the ninth against Paige. With two strikes, Mantle decided to try for a bunt single. In the book “Voices From Cooperstown,” Mantle said a bunt made sense to him because Paige “couldn’t hardly get off the mound.”

“I knew that if I could poke it past him I could beat him to first base,” Mantle said to the New York Times.

Instead, Mantle fouled the ball back to the screen on the bunt attempt, striking out. (More than a decade later, according to the Times, Mantle’s decision to bunt still rankled Whitey Ford. “That was a really stupid play,” Ford told Mantle. “I was so mad at you.” Mantle replied, “I still say it’s not necessarily such a bad play.”)

Paige retired Yogi Berra for the second out, but Gene Woodling singled, bringing Gil McDougald to the plate. Paige fell behind in the count, then got McDougald to pop up in foul territory, but catcher Les Moss dropped the ball.

McDougald fouled off two more pitches. As the Globe-Democrat noted, Paige “got the last bit of good theatre and ham out of the situation.”

With the count 3-and-2, McDougald popped up again _ this time in fair territory, near the mound. Marty Marion, who hadn’t made a play all night, rushed over from his spot near third base and caught the ball for the final out.

In the jubilant clubhouse, Satchel Paige said to the Associated Press, “Man, there’s no team I like to beat better than them Yankees.” Boxscore