Cardinals rookie Herman Bell seemed an unlikely candidate to accomplish one of the franchise’s most remarkable pitching feats.

One hundred years ago, on July 19, 1924, Bell pitched two complete games in a doubleheader and won both against the Braves at St. Louis.

One hundred years ago, on July 19, 1924, Bell pitched two complete games in a doubleheader and won both against the Braves at St. Louis.

Before joining the Cardinals, Bell primarily had been working as a cowpoke on a cattle ranch and pitching on pasture diamonds for semipro teams.

He went on to pitch in three World Series and have a role in one of Babe Ruth’s epic clouts.

Soldier and cowboy

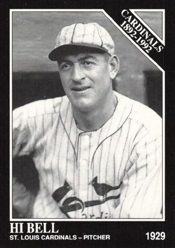

Herman “Hi” Bell was born in Mount Sherman, Ky., 10 miles from Abraham Lincoln’s birthplace in LaRue County, but moved with his family to northwest Iowa when he was a youngster.

(When he joined the Cardinals, his teammates nicknamed him “Hi,” from the expression, “Hiya, how’re you doing?” according to Sid Keener of the St. Louis Star-Times.)

Bell attended school in Sibley, Iowa, 10 miles from the Minnesota border, and also resided in Alton, Iowa, according to The Sporting News.

In 1917, when he was 19, Bell enlisted in the Army during World War I and completed his service in 1919. He then worked on a ranch in Colorado for three years (1919-21), the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported, and played semipro baseball for town teams in Iowa, Minnesota and South Dakota.

Bell expected “to become a regular cowboy for the cattle ranch” near Colorado Springs, according to the Alton (Iowa) Democrat.

“There are probably no baseball pitchers in northwest Iowa the superiors of Herman Bell,” the Alton Democrat noted in October 1921. “He has no ambition, however, toward entering professional baseball, and has already tried ranch life and likes it.”

Bell apparently had a change of heart, because in 1922 he played for the Sioux Falls (S.D.) Soos of the Dakota League in the Class D level of the minors. When the league folded in 1923, Bell went back to pitching for a semipro team and was discovered by Cardinals scout Charley Barrett, who signed him late that summer, according to the Globe-Democrat.

After a good spring training with the 1924 Cardinals, managed by Branch Rickey, Bell, 26, was on their Opening Day roster.

Starting out

A 6-foot right-hander, Bell’s first six appearances for the Cardinals were in relief and he wasn’t particularly impressive, allowing runs in four of those games.

Then he got a start, in the second game of a doubleheader against the Pirates at Pittsburgh, and pitched into the 15th inning before allowing the winning run. “The youngster pitched exceptionally well,” The Pittsburgh Press reported. Boxscore

Five days later, on June 4, Bell got his first win, pitching a complete game versus the Phillies at Baker Bowl in Philadelphia. Then he lost his next three starts, giving him a 1-4 record. Boxscore

Double wins

The Cardinals faced consecutive home doubleheaders _ Saturday, July 19, against the Braves and Sunday, July 20, versus the Phillies.

For Game 1 of the first doubleheader, Rickey chose Bell to start for the Cardinals (34-49) against the Braves (33-50).

Bell, who entered the game with a 4.80 ERA, retired the first 22 batters in a row before Ernie Padgett lined a double to right with one out in the eighth. Cotton Tierney followed with a single, scoring Padgett, but those were the only hits the Braves got versus Bell. He completed the two-hitter, a 6-1 Cardinals victory. The Braves’ No. 3 batter, Casey Stengel, went hitless. Boxscore

Between games, Rickey had Allen Sothoron and Bill Sherdel warm up, presumably with the notion of starting one of them in Game 2, but then the manager had an idea. He asked Bell whether he wanted to pitch the second game.

According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Bell replied, “Sure.” Rickey said, “Well, then, you’re the pitcher. Go to it.”

Rickey told the newspaper, “My purpose in sending Bell back was to instill confidence in the youngster and to give his teammates greater confidence in their pitcher. He is a big, strong lad and his pitching motion is such that pitching 18 innings entails no great effort.”

Bell retired the first 13 batters in Game 2. Just as in the opener, Ernie Padgett doubled for the first hit against him.

With the Cardinals ahead, 2-0, the Braves made it tense in the ninth. After Stengel’s two-out single drove in a run, the Braves had runners on first and third, with Stuffy McInnis, a career .307 hitter, at the plate.

“A trying moment for a pitcher who’d worked 17.2 innings,” the Globe-Democrat noted.

McInnis hit a grounder to third baseman Specs Toporcer, who threw to second in time to retire Stengel for the third out. Boxscore

(An oddity of note: The Cardinals had seven baserunners thrown out attempting to steal. In Game 1, Braves catcher Mickey O’Neil nailed five runners, and in Game 2 Frank Gibson stopped two.)

The Post-Dispatch described Bell’s pitching as “sensational.” The Globe-Democrat added it “was all the more remarkable considering that it rained during the greater part of both games.”

Sportsman’s Park didn’t have lights then.

As the Post-Dispatch reported, “At one stage of the opener it appeared as if the teams would be lucky to play the full nine innings. In the fourth and fifth innings of the nightcap, the ball was difficult to follow because of the darkness caused by the low black clouds rolling out of the west.”

Babe vs. Bell

Bell went winless the rest of the season, losing four more decisions, including an Aug. 6 start against the Braves, and finishing 3-8.

He spent the next year in the minors, with the 1925 Milwaukee Brewers.

Back with the Cardinals in 1926, Bell was a reliever and spot starter for a team that won the franchise’s first National League pennant and World Series title. In 19 relief appearances, Bell was 3-2 with a 1.27 ERA.

Bell’s lone appearance in the 1926 World Series against the Yankees came in a Game 4 relief stint at St. Louis _ and it was a doozy. In the sixth inning, Bell faced Babe Ruth, who had slugged home runs against starter Flint Rhem in the first and third innings. No one had hit three homers in a World Series game.

Bell worked the count to 3-and-2, then challenged The Babe. “Ruth waded into the fastball and put all his shoulders and back behind the 52-ounce bat,” the New York Times reported. “He caught the ball as flush as an expert marksman.”

As the New York Daily News noted, when Ruth made contact with Bell’s pitch, there was an “ominous crack, as loud as a rifle report” and the ball took off “as though propelled by high-powered explosives.”

This wasn’t one of Ruth’s arcing rainbows. It was, as the Daily News described, a “streak shot straight for the bleachers in center field, a direct flight.”

According to the Times, “It is 430 feet to the bleacher fence. The wall is about 20 feet high. Back of it stretches a deep bank of seats, and almost squarely in the middle of this bank” is where Ruth’s home run landed.

The Associated Press reported, “It was a terrific smash. The spectators just gasped and fell back in their seats.” Boxscore

Deja vu

Bell spent 1927 with the Cardinals, then most of the next two seasons (1928-29) with their farm club at Rochester, N.Y. On the final day of the 1928 season, with Rochester needing two wins at Montreal to clinch the International League pennant, manager Billy Southworth started Bell in both games of a doubleheader. He won both, replicating the feat he achieved with the Cardinals four years earlier.

In 1930, Bell’s last season with the Cardinals, he led the National League in saves (eight) for the pennant winners.

After another year at Rochester in 1931, Bell was drafted by the Giants and pitched three seasons for them, including 1933, when he had six wins, five saves and a 2.05 ERA for the World Series champions.

In 1935, Bell, along with Jim Thorpe, had an uncredited role as a ballplayer in “Alibi Ike,” a movie about a rookie pitcher for the Cubs with a penchant for making excuses. It starred Joe E. Brown, Olivia de Havilland and William Frawley, with Ring Lardner credited as a screenwriter.

After the 1937 season, when the Reds were looking for a manager to replace Chuck Dressen, Bell applied for the job, the Associated Press reported. Reds general manager Warren Giles, who had been Rochester club president when Bell pitched there, instead hired Bill McKechnie.

Bell operated a restaurant in Glendale, Calif., until his death from a heart attack at 51 in 1949.