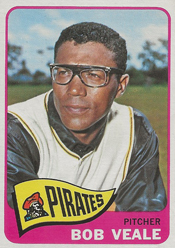

A big man with poor eyesight, left-hander Bob Veale threw as hard as any pitcher in baseball. He had one of the best sliders in the game and a fastball, as Sports Illustrated put it, “that leaves a vapor trail.”

Standing 6-foot-6 and weighing 220 to 280 pounds, Veale made some of the National League’s best hitters look inept. Lou Brock (.194 in 93 at-bats), Willie McCovey (.188 in 48 at-bats) and Ernie Banks (.108 in 83 at-bats) had career batting averages below .200 against Veale.

Standing 6-foot-6 and weighing 220 to 280 pounds, Veale made some of the National League’s best hitters look inept. Lou Brock (.194 in 93 at-bats), Willie McCovey (.188 in 48 at-bats) and Ernie Banks (.108 in 83 at-bats) had career batting averages below .200 against Veale.

Their figures seemed robust, however, compared with those of Eddie Mathews. A slugger who totaled 2,315 hits, including 512 home runs, Mathews was hitless in 29 career at-bats versus Veale, striking out 16 times. Asked by The Pittsburgh Press in 1964 to compare Veale with Sandy Koufax, Mathews said, “Koufax has the better curve; Veale the better slider. I wouldn’t want to earn a living batting exclusively against either one.”

Nevertheless, Mathews said Juan Marichal was the toughest pitcher he faced, according to the Baseball Hall of Fame Yearbook. Banks picked Koufax. Brock and McCovey chose Veale.

In his autobiography, “Stealing Is My Game,” Brock said of Veale, “He just gave me fits … He could blow the ball past me like I was a birthday candle. He threw about as hard as anyone I ever faced in the major leagues.”

Veale wanted to play for the Cardinals when he turned pro. Instead, he joined the Pirates after the Cardinals opted for another left-hander, Ray Sadecki.

An 18-game winner in 1964 when he led National League pitchers in both strikeouts (250) and walks (124), Veale was 89 when he died on Jan. 7, 2025.

Steely determination

A pitcher who spent most of his big-league playing career in the Steel City of Pittsburgh, Veale was from the steel capital of the south, Birmingham, Ala.

Veale grew up in the family home on Lomb Avenue, a few blocks from Rickwood Field, the ballpark of the minor-league Birmingham Barons and the Negro League Birmingham Black Barons. His father pitched in the Negro League.

As a gangly youth, Veale spent his free time at Rickwood Field, doing jobs for Barons general manager Eddie Glennon. He worked in the concession stand and sometimes pitched batting practice. Among the players he saw there was a Black Barons outfielder, Willie Mays.

Veale was a teen when he pitched for the 24th Street Red Sox, a top industrial league team. He got an athletic scholarship to play baseball and basketball at St. Benedict’s College in Atchison, Kansas.

(Located on a bluff overlooking the Missouri River, St. Benedict’s College merged in 1971 with Mount St. Scholastica College and became Benedictine College.)

As a college basketball center, Veale showed “some of the smoothest post play the conference has seen in many years,” the Atchison Daily Globe reported. The New York Times described him as “the Bill Russell type,” because of his rebounding. In a charity game, Veale guarded Kansas center Wilt Chamberlain.

Baseball was the sport, though, that offered Veale the best chance at a pro career.

While in college, “I listened to every Cardinals game I could,” Veale told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. He was elated when the Cardinals invited him to St. Louis for a tryout during his junior year in 1958.

The Cardinals, though, became enamored of another hard-throwing left-hander, Kansas high school pitcher Ray Sadecki. After they signed Sadecki to a big bonus, the Cardinals offered Veale much less _ minor-league money, “a few doughnuts, a couple of bats and some spikes,” Veale told the Post-Dispatch.

Tired of haggling with the Cardinals over money and feeling slighted _ “I knew Sadecki didn’t throw any harder than I did,” Veale said to reporter Neal Russo _ Veale tried out with the Pirates while they were in Chicago and signed with them.

Swinging and missing

Four years later, in 1962, Veale, 26, reached the majors, gaining a spot on the Opening Day roster. When the Pirates went to San Francisco to play the Giants, Willie Mays invited Veale and fellow Pirates rookie Donn Clendenon to his home after a game. According to The Pittsburgh Press, Mays advised Veale, “With your stuff, all you have to do is rear back and throw. Don’t mess around and be cute, trying to find the corners. You can throw hard enough to fool anybody and all you have to do is get the ball over.”

After two months with the 1962 Pirates, Veale was sent back to the minors. Pitching for Columbus (Ohio), he struck out 22 Buffalo batters in nine innings.

Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh used Veale as a reliever in 1963 and he dazzled (0.70 ERA in 27 games). Moved to the rotation in late August, Veale made seven starts, pitched two shutouts, including one against the Cardinals, and completed the season with an 0.93 ERA. Boxscore

That performance vaulted Veale to the top of the Pirates’ rotation in 1964. On a staff with Bob Friend and Vern Law, Veale got the Opening Day assignment and pitched like an ace that season. He struck out 16 in a game against the Reds and 15 versus the Braves. Boxscore and Boxscore

Entering the final day of the season, Veale had a league-leading 245 strikeouts and the Cardinals’ Bob Gibson was at 243. Neither was scheduled to start that day. However, during the Pirates’ game at Milwaukee, Veale learned that Gibson had relieved starter Curt Simmons during the Cardinals’ game with the Mets.

Concerned Gibson might surpass him to become the 1964 National League strikeout leader, Veale approached teammate Jerry Lynch, who was managing the Pirates that day. (With nothing at stake in their game with the Braves, Danny Murtaugh took the day off and let Lynch manage. Braves skipper Bobby Bragan did the same, having Eddie Mathews manage the club.)

According to the New York Times, Veale asked Lynch, “How about letting me pitch two innings and pick up a few (strikeouts)?” Lynch said yes.

With the Braves ahead 6-0, Veale pitched the sixth and seventh innings and struck out five consecutive batters, boosting his season total to 250. Gibson worked four innings and fanned two, giving him 245, and got the pennant-clinching win for St. Louis. Boxscore and Boxscore

Veale played a part in the Cardinals finishing in first place, a game ahead of the Phillies and Reds. He was 1-2 against the 1964 Cardinals and a combined 6-1 versus the Phillies and Reds.

Blinding speed

In a stretch from 1964-66, Veale lost six in a row to the Cardinals. Then he went 3-0 against them in 1967, the year the Cardinals became World Series champions.

Veale’s vision in his right eye was minus-2/20. In his autobiography, Lou Brock said, “He wore glasses that looked like the bottom of Coke bottles.”

In a game at St. Louis in May 1967, Veale had a 1-and-2 count on Brock and was wiping his glasses when a lens broke. Plate umpire Doug Harvey ordered Veale to pitch without the spectacles until a spare could be brought from the clubhouse, but Brock refused to stand in the batter’s box until Veale put on eyeglasses. “Even when he could see, Veale had trouble finding the plate with his pitches,” Brock explained in his autobiography.

Veale told the Post-Dispatch, “I can’t blame Brock. I see six people when I’m not wearing glasses.”

When the replacement pair arrived, after a lengthy delay, Veale struck out Brock on the next pitch. Boxscore

“Veale has developed one of the best sliders in the game,” Brock told the St. Louis newspaper. “I’ve always felt that for the first four or five innings, for sheer speed, he was faster than Sandy Koufax.”

According to the New York Times, after Veale struck out 16 Phillies in a game, their manager, Gene Mauch, said, “I’ve never seen such sustained fire.” Boxscore

Big Bob

From 1964-67, Veale had season win totals of 18, 17, 16 and 16.

Eventually, though, he didn’t stay in shape, gained too much weight and was moved to the bullpen. In 1971, when the Pirates became World Series champions, Veale was 6-0 but his ERA ballooned to 6.99. He spent most of 1972 in the minors before the Red Sox acquired him in September that year.

When he tipped the scales at 230 pounds in 1974, Veale told the Birmingham Post-Herald, “Two-thirty is a lot better than coming in at 280. I did that at Pittsburgh. When I came to Boston (in 1972), I came in at between 260 and 270.”

The 1973 Red Sox pitching staff included Luis Tiant (20 wins) and Veale (11 saves). Peter Gammons of the Boston Globe noted that Tiant and Veale could be found smoking cigars in the clubhouse whirlpool.

Veale completed his big-league career with a 120-95 record, 20 shutouts, 21 saves and 1,703 strikeouts in 1,926 innings. His 1,652 strikeouts with the Pirates are the most by a Pittsburgh left-hander. Veale averaged eight strikeouts per nine innings with Pittsburgh.

After a stint as a minor-league pitching instructor, Veale resided near the Rickwood ballpark in Birmingham “and often just shows up to help take care of the field,” the Birmingham Post-Herald reported.