In late July 1944, Allied troops were on the outskirts of Brest, a strategic seaport town in northwest France that the Germans occupied during World War II and turned into a submarine base. The Allies were determined to drive out the Nazis, and hoped to make the harbor a supply hub.

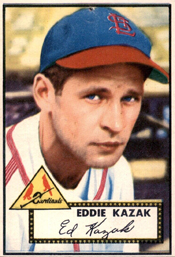

Among the infantry advancing on Brest was a U.S. Army private, Eddie Kazak, a St. Louis Cardinals infield prospect. In the combat that ensued, Kazak had a bayonet driven through his left arm and had his right elbow crushed during an artillery attack. It took more than a year for him to recover. Discharged in December 1945, doctors warned him against playing baseball again.

Among the infantry advancing on Brest was a U.S. Army private, Eddie Kazak, a St. Louis Cardinals infield prospect. In the combat that ensued, Kazak had a bayonet driven through his left arm and had his right elbow crushed during an artillery attack. It took more than a year for him to recover. Discharged in December 1945, doctors warned him against playing baseball again.

Four years later, Kazak was the Cardinals’ rookie third baseman and the starter for the National League in the 1949 All-Star Game.

Dangerous work

A son of Polish immigrants, Edward “Eddie” Tkaczuk was born in Steubenville, Ohio, and raised in Muse, Pa., 20 miles south of Pittsburgh. His father, Joseph Tkaczuk, was a coal miner, working “down deep where the sun and fresh air are withheld by earthen barriers as formidable as prison bars,” Bob Broeg wrote in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

After Eddie graduated from high school, he joined his dad as a coal digger. “To blink his way into the daylight and up to the cashier’s cage above ground for $50 checks every two weeks, he had to load 130 or more tons,” Broeg reported.

One day, a coal car, swinging around a bend too fast, jumped a rail, overturned and pinned Eddie against a tunnel wall, cracking several ribs.

When he recovered, Eddie, 19, resumed playing amateur baseball, including on Sundays for the coal mine team. He got an offer to turn pro with the Valdosta (Ga.) Trojans, a Class D minor-league club with no big-league affiliation.

Eddie wanted to sign but sought approval from his father because it meant giving up the steadier income he shared with the family from mining. “Papa Tkaczuk was eager for his son to have an opportunity to spend his life above ground at an easier task,” Bob Broeg wrote. “The boy was given parental blessing.”

Purple heart

A second baseman who hit for average, Eddie played for Valdosta in 1940 and impressed Joe Cusick, manager of the Cardinals’ Albany (Ga.) farm team. On Cusick’s recommendation, the Cardinals bought Eddie’s contract for $1,000 and brought him into their system. He batted .378 with 221 hits for Albany in 1941.

While with the Houston Buffaloes in 1942, Eddie met Thelma Bee Gregg and they became a couple. After the season, Eddie, 22, enlisted for military duty and went into the Army. That’s how he ended up in France in the summer of 1944.

The Germans fortified their defenses at Brest and the fighting was intense. In hand-to-hand combat with a German soldier, Eddie was knocked to the ground. He rolled over as the attacker rushed forward and thrust a bayonet through Eddie’s left arm, just missing an artery. “I think I shot him then because suddenly I was free,” Eddie said to Bob Broeg.

The wound required 19 stitches and left a huge scar.

Two weeks later, during an advancement, Eddie came under heavy fire. Shell fragments rained all around, striking Eddie and bringing down a structure he was near. He was buried in bricks and his right elbow, the one he used for throwing a baseball, was shattered.

Eddie spent the next year and a half in military hospitals. Doctors wanted to amputate the arm but he was against it. “For nearly a year of that time, his right arm was shaped like a capital ‘L’ and he couldn’t move the first three fingers of his right hand,” Broeg reported. “Then there was a delicate operation. Pieces of crushed bone were removed and plastic was used to repair the shattered elbow.”

Movement returned to the fingers, but when he was cleared to return to civilian life, Eddie, 25, had to weigh the advice of doctors against his desire to resume his baseball career. “I was warned to give up baseball because throwing might dislocate the synthetic elbow,” he told the Associated Press. “The doctors also said that, if the elbow should lock, there was nothing they could do about it.”

Eddie thought it over and chose baseball.

Lots of changes

In 1946, Eddie married Thelma Bee Gregg and they settled in her hometown of Austin, Texas. He took an off-season job as a postman, delivering mail. “I like the walking, the exercise,” he told Broeg. He also chose a simplified spelling of his last name, changing Tkaczuk to Kazak. As broadcaster Harry Caray might say, Kazak spelled backwards is still Kazak.

Kazak came to 1946 spring training to play second base in the Cardinals’ system but almost quit. He told the Newspaper Enterprise Association, “I couldn’t throw or swing properly. The pain killed me.”

He did daily exercises to strengthen his right arm and gradually made enough progress to perform. He also changed his batting style to compensate for the damaged arm, moving his hands up the handle and using a choked grip. Broeg described him as a good wrist hitter, “meaning Kazak can delay his swing until the last second and then snap into a pitch, buggy-whipping the ball.”

As the Newspaper Enterprise Association noted, “His powerful wrists make him an extraordinary line drive hitter. He gets the bat around so quickly that he gives the impression of jerking the ball out of the catcher’s glove, pulling it into left field.”

Kazak’s hitting kept him in the game. He made 47 errors at second with Columbus (Ga.) in 1946, but batted .326 with 88 RBI in 93 games for Omaha in 1947.

Promoted to Class AAA Rochester in 1948, Kazak was moved to third base by manager Cedric Durst. “I hate to have to pivot and make those snap throws (at second),” Kazak told the Associated Press. As the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette noted, “The throw from third is longer but it is easier for Eddie to make.”

After hitting .309 with 85 RBI for Rochester in 1948, Kazak, 28, got called up to the big leagues in September and made his debut with the Cardinals. He got six hits, including three doubles, in six games.

Opportunity knocks

After Cardinals third baseman Whitey Kurowski had bone chips removed from his right elbow late in the 1948 season, he came to training camp the following spring and was unable to throw, opening the door for Kazak to make the team.

The 1949 Cardinals began the season with rookie Tommy Glaviano as the third baseman and Kazak as backup. When Glaviano struggled to hit, Kazak became the starter in the fifth game of the season. Kazak hit .385 in April and .359 in May.

On May 5, Cardinals second baseman Red Schoendienst was injured and Kazak replaced him, starting five games at second. It didn’t hurt his hitting. On May 9, he slugged his first big-league home run, a grand slam versus the Dodgers’ Joe Hatten at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. Boxscore

Two months later, Kazak was back in Ebbets Field as the National League starting third baseman for the All-Star Game. Kazak was selected ahead of the Giants’ Sid Gordon and the Braves’ Bob Elliott in fan balloting. “It’s the greatest thrill I’ve ever had,” Kazak told The Sporting News.

(The National League all-star catcher was the Phillies’ Andy Seminick, who, like Kazak, grew up in Muse, Pa.)

Kazak went 2-for-2 in the game _ a single against Mel Parnell in the second and a RBI-single in the third versus Virgil Trucks.

He also was involved in a fielding controversy in the first. After scooping up a George Kell grounder, Kazak made a low throw to first baseman Johnny Mize, who dropped the ball. According to umpire Cal Hubbard, Kell would have been out if Mize had held onto the ball. Official scorer Roscoe McGowen charged Kazak with the error, but later reversed his ruling, giving Mize the error instead. Boxscore

Painful slide

Two weeks later, the Cardinals (52-36) were in Brooklyn to play the first-place Dodgers (53-34). Facing Joe Hatten again in the second inning, Kazak drove a ball to deep center. It smacked against the wall and caromed directly to center fielder Duke Snider.

Kazak, not expecting the ball to get to Snider so quickly, initially thought he had a stand-up double. “I realized all of a sudden I had to slide,” he recalled to the Austin American-Statesman. “I was too close to the bag for a normal slide and I plowed right on through the cushion, breaking the strap and separating the bag from the iron pin.”

Kazak writhed in pain and was carried on a stretcher to the clubhouse. “I was scared to death because it hurt way up into my hip,” Kazak told the Austin newspaper. Boxscore

He suffered chipped bones in his right ankle, jamming it where it fits the socket, and was unable to play the remainder of July and all of August.

On Labor Day, Sept. 5, 1949, the Pirates led the Cardinals in the seventh inning at St. Louis when Kazak made a surprise appearance, hobbling to the plate to bat for pitcher Ted Wilks. The holiday crowd responded with a thunderous ovation. In a game for the first time since injuring his ankle, Kazak swung at the first pitch from Bill Werle and whacked it into the bleachers in left for a home run.

“As he limped slowly around the bases, the roar of the crowd increased in appreciation,” The Sporting News reported. Boxscore

Kazak made four more pinch-hit appearances that month. For the season, he batted .304 (including .312 versus the Dodgers) and had an on-base percentage of .362. The Cardinals (96-58) finished a game behind the National League champion Dodgers (97-57). “We’d have won it with Kazak in the lineup all season,” Cardinals manager Eddie Dyer said to the Austin American-Statesman.

In October, Kazak had an ankle operation. He was the 1950 Cardinals’ Opening Day third baseman. He started again the next night, made three errors and didn’t start again until June.

After beginning the 1951 season with the Cardinals, Kazak was demoted to the minors in May. A year later, he was dealt to the Reds. He appeared in 13 games for them and spent the rest of his playing days in the minors.