The narrative is that this market is CRAZY

Today I’m taking a look at off-season Free Agent activity, particularly of the starting pitcher variety. Of the 14 pitchers that have signed so far, 6 of them (Snell, Wacha, Martinez, Flaherty, Manaea, Severino) are returnees from last year’s market, so we should be able to make some comparisons and draw some conclusions. Did I mention that all the pitchers but one (Buehler) are 31 or older?

What happened to the narrative that a WAR has a street value of around $8m? And what happened to the narrative that peak production happens around 26-27 and decline accelerates at around 31? And what happened to the narrative that WAR declines by about .5 WAR each year during decline? Don’t these signing teams know these narratives? What is going on? Signing all these old guys. Sheesh!

A sidebar: Where economics and sociology collide, there is a phenomenon where people remember (or think they do) what the price of something was back when. Like I remember buying gas at $.54 per gallon. People’s view of inflation and reasonableness of price is often relative to that ancient (and sometimes incorrect) memory. So, when gas hit $4.29 per gallon in 2022, we see 800% inflation from that $.54 and bemoan what has happened with prices. Craziness! They call this “price shock”. What people commonly lose track of is little details. Like when I was 16 (first year buying gas), average cost was really $.64/gallon, today it is $2.31/gallon (at Costco) and that translates to something like 2.3% inflation over 50-year time span, which is lower than general inflation over the same time period. Hardly crazy. Remember that when you look at Fried’s $218m contract. That is the baseball version of price shock.

Before we get to the cost side of the pitching equation, let’s take a quick peak at performance, via pitching WAR and aging curves for a moment.

When I first queried pitchers, I looked at all pitchers. Turns out, the average WAR for all pitchers is about 1.5 every year. I realized that most of those guys aren’t influencing this market. I narrowed my queries quite severely. I took only notable pitchers who were/are starters. From what I can glean, you have to be a notable pitcher (starters > 10 career WAR) to be able to play in this market. The exceptions to this are Holmes (a reliever being converted to a starter?), and Kikuchi (not notable). Kikuchi was signed by the Angels, which is probably enough explanation. Everyone else has a notable baseline established.

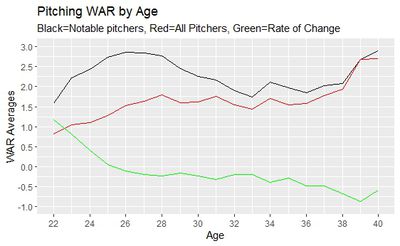

What do we see in the data? It appears that peak production does indeed occur at age 26-28 (peak average WAR of ~2.85. That narrative is validated. So, if peak occurs at 26-28, why are teams signing all these much older pitchers to high dollar contracts?

To explain this table a bit. Counting pitchers, totaling their WAR and getting an average by age was easy. I added a little embellishment. First, the Yr2YrChg column shows how each age cohort performed relative to 1 year earlier. As you see, the decline each year through age 38 is slight most years, never .5 WAR. But…this average is only for pitchers that pitched that year. What about the 10-20% that dropped out from prior year. Example: There were 151 pitchers at age 32, but only 136 at age 33. The 136 pitchers did not decline, but 15 of them produced 0 WAR, probably because they retired or were hurt.

So, I added the “Last Year” column to show the decline that included, in the average, the pitchers who pitched last year but did not pitch this year. Note that the decline rate still doesn’t materially differ until age 37. That tells me that the pitchers dropping of year-by-year were near zero even in their final year. The point? The average WAR data says that pitchers can reliably maintain their WAR production (with slight decline) well into their late 30’s. What declines at around 15% a year is the number of pitchers, not the performance. The performance declines reliably slowly and doesn’t hit .5 WAR/yr until age 37.

For those that prefer the picture, see the graph below. The black line is notable starting pitchers. Red is everyone. Green is my embellishment – the real rate of change. Note that even at advanced ages, the notable starters are above average.

Note how flat the rate of change is between ages 28 and 38. Hardly falling off a cliff. I think I’m seeing why these pitchers are getting the length of contract they are getting (mostly).

Let’s move to the cost side of the equation. Now that the big players are off the market, we can look and see what it all means. Let’s start with … based on the performance data, I would opine that the major risk with these players isn’t performance decline, it is injury. Teams can hedge that risk a bit with insurance. And let’s face it, injury risk exists at all ages. I don’t have the data, but I’d hazard a guess that pitchers on other side of 30 have as stable, if not more stable, injury experiences than younger pitchers. The contracts tell me this.

In this model, I carried each pitchers’ basic profile and projected their performance through the contact period based on the decline data from above. I applied the MLB approved discount rate to discount future payments back to net present value (NPV) so we can compare apples to apples. There appear to be roughly 3 tiers of performance and somewhat identifiable rates to go with the performance classes.

**You will have to scroll right to see all the data.

Even with the sample size being small, I think there may be some tiers and commonalities here we can identify that help make sense of this crazy market.

Before I get into the tiers, I notice a couple of things. Again, SSS alert here, but something to watch for. One is the mix of LHP and RHP being signed to large contracts is not particularly close to the ratio of LHP and RHP pitchers in the league. The limited data suggests LHP get a bit of a premium. For example, career FIPs of 4.01 FIP belong to Manaea and Wacha, who are similar age, similar career WAR and both pitchers signed FA contracts in both 2024 and 2025. Manaea got the bigger contract both times (in $$ per WAR, NPV). Likewise, LHP Snell outpaces his RHP counterparts (Nola last year, Cole this year) while having a bit higher career FIP.

Second, factoring an LHP premium, the group sorted by career FIP lines up pretty well with the group sorted on $$ per WAR (NPV) (last column). The top guys (Fried, Cole, Snell, Burnes have career FIP 3.51 and below. The other guys have higher FIP than that and all have lower contract points, best illuminated in $$/WAR NPV. What I see is the contracts pretty much seem to reflect career FIP (except for Kikuchi). I’ll call him the “Angels on the Mound” effect.

Third, most of the contracts are 3 years, with a couple longer contracts going to pitchers on the younger end. Noted.

Tier 1 – In 2024/25 offseason, the first tier is the top 4 contracts. These are the guys that could realistically project to have a 3 WAR (or plus) season and decline from there. Cole, Snell, Fried, Burnes. Each has some different variables. Length, total committed, AAV. There are no pesky deferrals, but the Dodgers outdid themselves with that $52 million bonus paid to Blake Snell day 1. I sense they have discovered ways to game the system by putting major $$ either up front or way in the future. They are all guaranteed contracts, so perhaps the only material difference is when the check is written.

I see some similarities even in this small group as well as compared to the larger group. The 4 signed in this off-season are notable, established pitchers with relatively high (compared to average) career WAR and recent performance. Career FIP below 3.50. Only Fried’s contract runs into the major decline years. When you factor in the MLB discount rate, the NPV per WAR for these 3 WAR pitchers is in the range of $12m/WAR, skewed a bit by the outsized bonus to Snell.

If you look at 2024, similar story with Nola and Snell (again). Nola looks a scad low in $$ Per WAR (NPV), but it may be that my projected performance was rosier than the Phillies.

Overall, this very small tier (in terms of players) saw a robust pay growth from $10m/yr (NPV) to something more like $11.5m/yr (NPV).

Tier 2 – This second tier are guys more around 2.5 WAR projected. It has Severino, Manaea, Kikuchi, Wacha, Martinez. Again, different variables with each contract, but some common ingredients. Career FIP between 3.5 and 4.10. Except Kikuchi. All established notable pitchers, except Kikuchi. Age 31-34. All figure to be between 2-3 WAR (except maybe Kikuchi) and decline from there. Length for this group all around 3 years. If I throw out Kikuchi on the assumption that the Angels had to massively overpay to attract him, the grouping seems solid and the NPV per WAR for these ~ 2.5 WAR pitchers ends up around $8.5m +/- $1m per WAR (NPV).

Peeking into last year’s FA group, this tier looks similar. I’d eyeball it as $7.5m +/- $1m, versus $8.5m +/- this year, so closer to a 20% gain for this group, too.

I’d have to research further back, but I’m suspecting that clubs (and the market) are valuing older pitchers WAR now more so than before. Perhaps because of less drastic decline curves among the over-30 crowd.

Tier 3 – The oddballs. What to make of Buehler? He of the 2024 WAR value of -.2 coming off his second TJ surgery. The rate of successful return on those is like 33%. How would you project his WAR? Or Holmes, a reliever all his life now being paid more like a starter.

Tier 4 – Everyone else (who mostly haven’t signed yet). I expect this group will start to fill in after the holiday. I don’t expect much length in these contracts, so discounting won’t be much of a factor. For some reason, I expect the AAV of this group to be higher, but the length of contract to be lower than Tier 2. I’d also expect these will be the guys that teams will view as 2 or less WAR pitchers coming in. Think Kyle Gibson from last year. Teams will pay a premium for some lower-level certainty (ala. Gibson), more than they would the oddballs. With these guys, the play is more for stability and innings than FIP values. We will have to wait and watch the market play out on this group.

Overall

With a very limited sample size, it appears that $$ per WAR (on an NPV basis) isn’t a constant $8m/WAR for starting pitchers. It looks like about each .5 increment of WAR a pitcher can produce seems to result in a higher $/WAR value paid, so a non-linear curve. A power curve?

I see a floor both in the contract data and performance data of about 1.0-1.5 WAR, suggesting an older pitcher who isn’t expected to hit that floor is going to be replaced by a league-minimum pitcher or pitchers making a few million in their arb-eligible years (this would be Tier 5).

It’s also not clear that rates have markedly changed over longer periods than just the last two years and with a larger sample. There may be too few sample points to draw too much conclusion yet, but in the top tier, Cole’s NPV $/WAR was established years ago at $11.5m/WAR and that puts him right in the range of Tier 1 today. Snell was at $10.2m/WAR last year, having to sign a contract late with little leverage, and upped this year to over $12m/WAR. That value is heavily influenced by the front-load nature of the contract. Is there also some Snell rebuilding value in 2024 that raised his value intrinsically this off-season, and not so much an inflationary effect across the market?

What we see in the data is that if a pitcher in his 30’s pitches well in a season, he is 80% likely to repeat with only a .1 or .2 decline in WAR on average. The 20% of pitchers that fall off the radar are ones who produced well below the 1.5 floor in their last year, so teams can see them coming. Heck, almost 50% of the pitchers would be expected to be producing within a .5 WAR of target even by year 3. Given this reliability data, we are most definitely seeing a period where teams are not afraid to invest major $$ in pitchers aged in their low to mid-thirties.

One variable I tracked where I couldn’t find a tangible impact (again, small samples) is if getting a QO affected what a team would pay. On the surface, it doesn’t appear to have much effect (at least this off-season), but there are only a few (Fried, Manaea, Martinez, Severino). All ended up in the range, but the sample is small enough that the QO ptichers play a large role in defining the range. Chicken or egg? If you peak back to 2023, all 3 pitchers who received (and declined QO) seem to have had their contract values depressed a little bit (Gray, Snell, Nola). Overall, hints about QO impacts, but nothing conclusive.

Last takeaway, which is really more of a question needing further research. I only looked at supply side (ie. the pitchers). There is a demand side component to this. It seems obvious that Tier 1 pitcher contracts are really the domain of big market teams (LA, NYY, NYM, SF, PHI). Is this right? So, what happens in a year when there are more Tier 1 pitchers than there are big market teams that need pitching? Conversely, what happens to that market when a sorta big market team (HOU, SD, BOS) decides to play with the big boys?

Since this is a Cardinal blog, I’ll throw in a couple of other observations:

- The Sonny Gray contract is not a bad deal. His performance fits in top tier, but Cardinals got him at the Tier 2 rate. Although some might question backloading $40 million into the last year, it’s still not an awful investment. He would project to still be a 3+ WAR pitcher in the last year and will likely be a candidate for the team option (if healthy).

- Erick Fedde. There has been lots of discussion about him. Although his performance history is not as deep as a typical FA, he would appear to be a Tier 2 pitcher by FIP, but his $7.5m contract for 2025 is low for that group. His is most definitely a below-market contract. Based on what I’ve put together here, he is going to go out on the market after next season as a 32-year-old RHP and do well for himself, likely something in the area of 3-4 yrs at around $8 or $9 million per year per WAR. $80-$90 million, guaranteed, maybe? Seems outlandish, but that is what the numbers suggest. If his performance holds in 2025, he will definitely be a QO guy. His baseline of FIP and WAR will be solidified (one way or the other) with his 2025 performance. I am imagining right now that teams inquiring about him see this value but would be reluctant to part with a real value prospect because they can be pretty sure they will only have him 1 year. In a normal year, he’d look more like an extension candidate than a trade candidate. Even if he is not extended, a declined QO would return a late 2nd round pick. That, to me, sets the absolute floor of his trade value.

- Miles Mikolas. Everyone’s favorite whipping boy. He is in the 3rd year of a 3-year extension for $57.75m. It was a bit front loaded, so they’ve paid him just over $40m for 5.1 WAR in the first two years, or ~$7.8m per WAR. That is market value. Recognize that a mid-market team needs to have surplus value in their mid-range contracts, so they have headroom to add talent. While this has not been a bad contract, it hasn’t been advantageous either. He is due $16m in 2025 and Steamer projects him for 1.8 WAR. That would put him at just over $8m per WAR. Maybe a tad high, but not seriously under water. Since it will be his age-37 season, and decline tends to be sharper at this age, I’d guess his final projection will be more like 1.5 WAR.

As stated, I recognize the small sample size factor here, so can’t put too many stakes too deep in the ground on this one. But this market is by definition all small samples, so we get to parse the data we have.

Discuss.